At either this meeting or a subsequent appointment, trained study staff members administered the 6-item Screener ( 22) and the full Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID) ( 23). At the consent appointment, they responded again to the 2 anxiety screening questions and completed a demographic questionnaire. We asked patients who expressed interest in participating 2 anxiety screening questions from the PRIME-MD ( 21) and scheduled those responding affirmatively to at least 1 of the 2 questions for an in-person visit to review the consent form. We also recruited patients through educational brochures in waiting and examination rooms.

A telephone call followed the letters to invite patients to participate in the study unless patients called to decline participation. With PCP approval, identified patients received a letter of invitation from the PCP and the senior author (MS) to participate in the study. We targeted patients with a documented EMR diagnosis of GAD or Anxiety Not Otherwise Specified for recruitment, as well as patients with anxiety symptoms noted on the problem list, or those having a prescription for anti-anxiety or antidepressant medication. Potential patients were identified in collaboration with primary care providers (PCP) through the electronic medical record (EMR) and by self-referral. DeBakey Veterans Administration Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine. From October 2008 to April 2012, 223 patients, age 60 and older, with Diagnostic & Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) GAD diagnoses ( 20) were recruited through internal medicine, family practice, and geriatric clinics at 2diverse healthcare settings: Michael E.

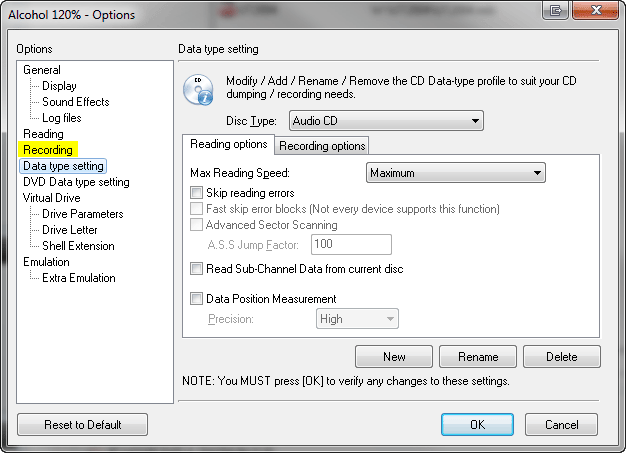

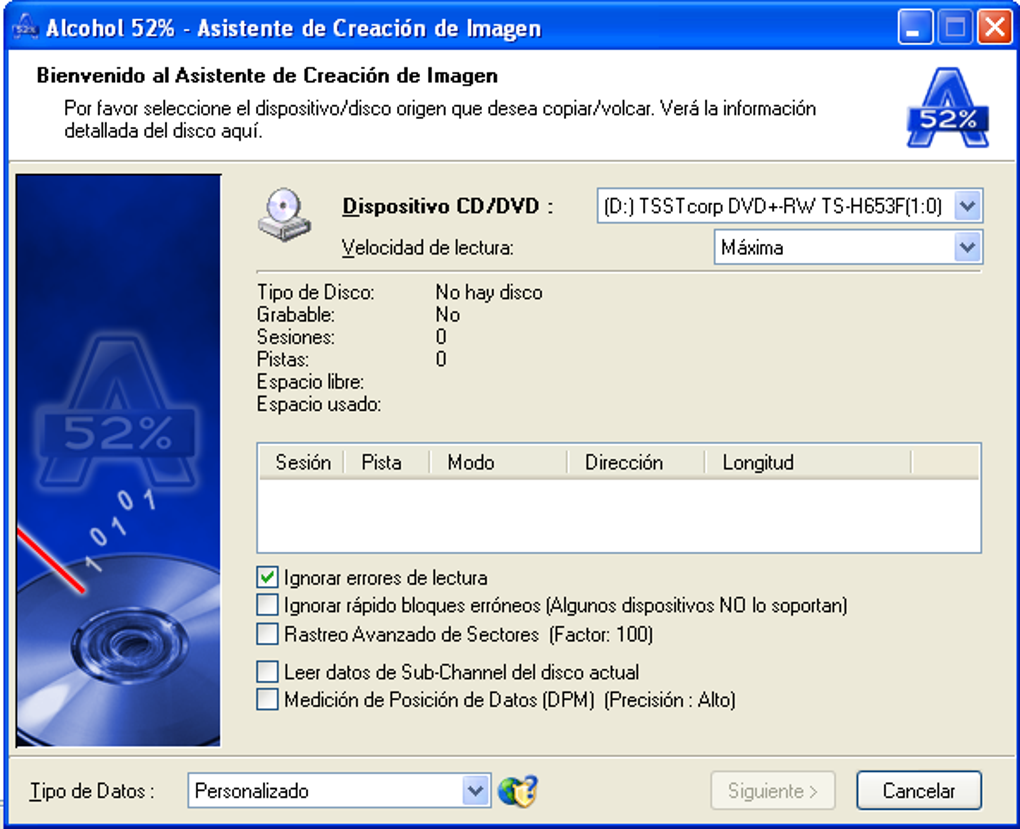

#How to use alcohol 52 free edition trial#

We drew the sample from a randomized, controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy among older primary care patients with GAD and used only baseline data from an ongoing clinical trial. We expected that alcohol use would worsen the relation between anxiety and insomnia, given that alcohol leads to more nocturnal awakenings ( 18, 19), which present increased opportunities for worry that likely delay return to sleep. A third aim of the study was to examine the moderating role of alcohol use on the relation between anxiety and insomnia. We expected alcohol - use distribution in our sample to be similar to that of previous reports with older adults in primary care ( 11) and we expected alcohol use to be associated with higher anxiety and insomnia, given prior literature demonstrating similar relations.( 11, 13).

The current study examined the presence and frequency of alcohol consumption among older primary care patients with GAD and the relation of these variables to demographic variables (age, gender, race, ethnicity, and education), insomnia symptoms, worry, and anxiety. However, aging, chronic alcohol use, and anxiety have a negative impact on slow-wave sleep. Slow-wave sleep is considered to be the most restorative aspect of sleep ( 16, 17). The combination of alcohol and anxiety may have an additive negative influence on sleep. There are overlapping changes in the sleep of the elderly ( 14), patients with anxiety ( 15), and patients with alcohol use. Although one study has examined the relation between alcohol use and insomnia among older adults ( 12), the study had limitations and did not examine the impact of alcohol on those with anxiety, who are at greater risk of experiencing insomnia ( 1).Īlthough acute alcohol use may promote sleep, tolerance to alcohol’s sleep-enhancing effects develops within 3−9 nights of daily use, and chronic alcohol use leads to disruption of the normal sleep pattern ( 13). Among older adults in primary care settings, 70.0% do not consume alcohol, 21.5% drink moderately (1−7 drinks a week), 4.1 % are at risk drinkers (8−14 drinks a week) and 4.5% are heavy drinkers or bingers (over 14 drinks a week) ( 11). Alcohol use among patients with anxiety may exacerbate anxiety and associated sleep problems by leading to fragmented, nonrestorative sleep. A significant number of older people with GAD (44% to 52%) have insomnia ( 2, 9).Īmong adult patients whose insomnia is chronic and untreated, alcohol is frequently used as a sedative ( 1, 10). Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is 1 of the most common anxiety disorders in older adults, with community prevalence from 1.2% to 7.3% ( 5, 6), and even higher rates in primary care ( 7, 8). Anxiety and insomnia are common in geriatric patients ( 1), and they share substantial overlap ( 2− 4).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)